Introduction and setting the context

Over the last month, the ThreatLabZ researchers have been actively monitoring a recent uptick in the numbers of Win32/Caphaw (henceforward known as Caphaw) infections that have been actively targeting users' bank accounts since 2011. You may recognize this threat from research done by WeLiveSecurity earlier this year in regards to this threat targeting EU Banking sites. This time would appear to be no different. So far, we have tied this threat to monitoring it's victims for login credentials to 24 financial institutions.

About Win32/Caphaw

The Caphaw trojan is a financial malware attack that functions similarly to the Carberp, Ranbyus, and Tinba threats according to analysis done by WeLiveSecurity Researcher, Alekandr Matrosov. These attacks are carried out utilizing stealth tactics both on and off the wire. Caphaw avoids local detection by injecting itself into legitimate processes such as explorer.exe or iexplore.exe, while simultaneously obfuscating its phone home traffic through the use of Domain Generated Algorithm created addresses using Self Signed SSL certificates. This limits the ability of traditional network monitoring solution to dissect the packets on the wire for any malicious transactions. Caphaw attacks major European banks and previous analysis has shown that the malware is most active in the UK, Italy, Denmark and Turkey. This is especially prevalent considering the mapped known infected nodes seen here.

The geoip (location) information derived from the infected host is of special significance to this malware. The malware leverages the following legitimate URL: hxxp://j.maxmind.com/app/geoip.js to discover geoip information about its freshly infected victim. Administrators should view this transaction as a starting point for their investigation into any suspicious activity. It is not a malicious service, but illustrates how malware writers can leverage even legitimate services. The infection uses the output of this script to extract location information about the infected host/victim.

The geoip (location) information derived from the infected host is of special significance to this malware. The malware leverages the following legitimate URL: hxxp://j.maxmind.com/app/geoip.js to discover geoip information about its freshly infected victim. Administrators should view this transaction as a starting point for their investigation into any suspicious activity. It is not a malicious service, but illustrates how malware writers can leverage even legitimate services. The infection uses the output of this script to extract location information about the infected host/victim.

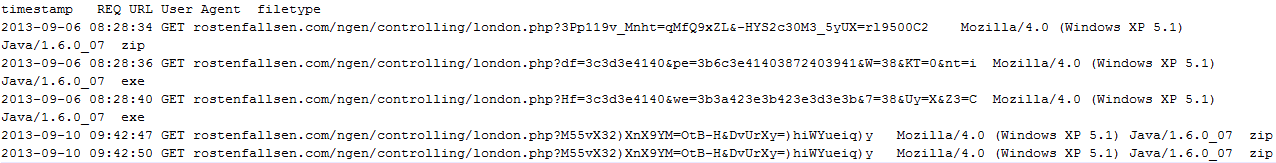

At the time of research, we were unable to identify the initial infection vector. We can tell that it is more than likely arriving as part of an Exploit Kit honing in on vulnerable versions of Java. The reason we suspect this is that the User-Agent for every single transaction that has come through our Behavioral Analysis (BA) solution has been: Mozilla/4.0 (Windows XP 5.1) Java/1.6.0_07.

|

| The UserAgent for known drop locations of this are manipulating users with Java version 1.6.07 |

The variation in the dropped executable is different across every instance, so its no wonder standard AV is having a problem keeping up (1/46 at time of research). This AV performance also indicates that the likelihood of someone proactively catching this infection inside their network is fairly low at the time of this writing.

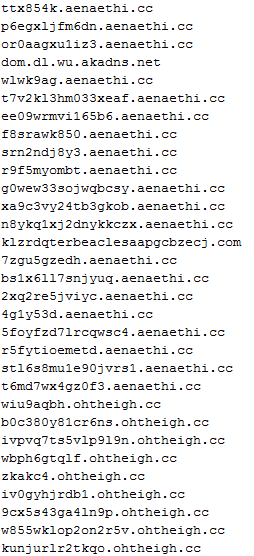

Use of DGA

A domain generation algorithm (or DGA) represents an algorithm seen in various families of malware to generate a large number of quasi-random domain names. These can be used to identify the malware's command and control (CnC) servers so that the infected hosts can "dial home" and receive/send commands/data. The large number of potential rendezvous points with randomized names makes it extremely difficult for investigators and law enforcement agencies to identify and "take down" the CnC infrastructure. Furthermore, by using encryption, it adds another layer of difficulty to the process of identifying and targeting the command and control assets.

Instance 1

cso0vm2q6g86owao.thepohzi.su

5qloxxe.tohk5ja.cc

k2s0euuz.oogagh.su

Instance 2

v8ylm8e.thepohzi.su

2g24ar4vu8ay6.tohk5ja.cc

d6vh5x1cic1yyz1i.oogagh.su

Instance 3

t2250p29079m6oq8.thepohzi.su

ngb0ef99.tohk5ja.cc

nxdhetohak91794.oogagh.su

The pattern ("ping.html?r=") is commonly known to be used by past versions of Caphaw. Don't panic straight away if you see this string in your user logs however as it is also commonplace among sites that use "outbrain.com" services. You'll want to look for any URI path that uses /ping.html?r= that does not contain "/utils/". Hopefully that helps narrow the search to see if you've encountered transactions similar to the following screenshot.

|

| DGA is used to hide the phone home activity of the initial detection |

Across all 64 distinct samples we've collected of this threat thus far, there have been 469 distinct IPs where there has been a call to a DGA location. A small sample of those illustrate the connection between the phone home data collected via network logs and the BA of the Caphaw samples.

|

| The DGA used here shows a connection between Caphaw phone home activity and Sandboxed samples of the threat in question |

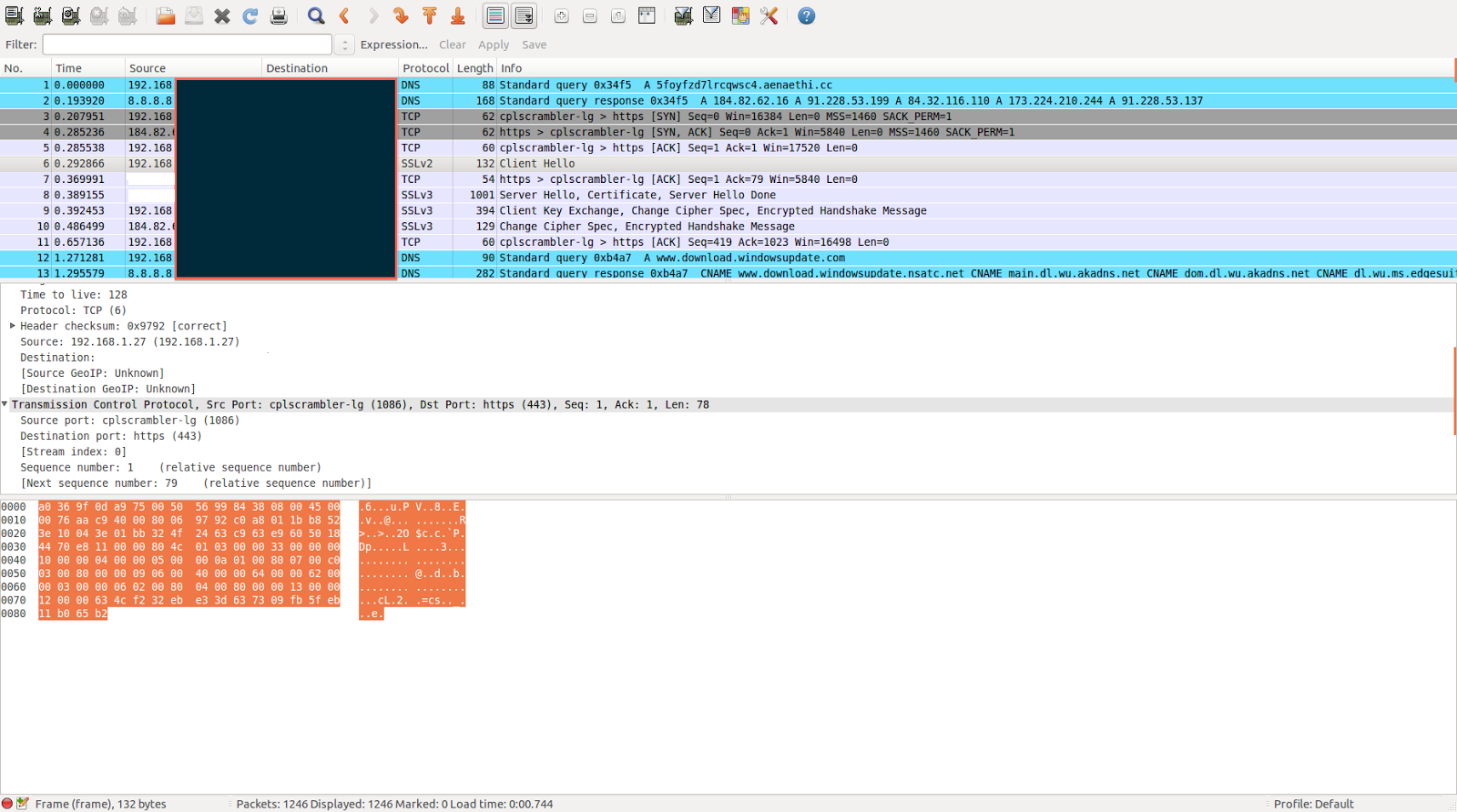

Use of SSL encrypted communications

The initial indicators were in the form of mysterious self-signed SSL traffic between end user hosts and various points of presence on the Internet, potentially components of the malware’s CnC infrastructure. See the screenshot below showing the self signed SSL cert. used in the malware communication:

Other screenshots below show the SSL handshake between the infected hosts and the remote CnC servers:

A binary executable (.exe) file is created in the attack sequence and masquerades as a .php file. This executable is created using Microsoft Visual C++ and the creator has not removed the debugging information from the final executable.

Both the location of where this file is dropped and the name of the file itself is selected quasi-randomly. For example, in one of the test instances we found this to be:

C: Documents and Settings\user\ApplicationData\Sun\Java\Deployment\SystemCache\6.0\9\typeperf.exe

During the three instances of malware execution we ran in our BA lab, we observed the following executables and their drop locations:

\Documents and Settings\%USER%\ApplicationData\Sun\Java\utilman.exe

\Documents and Settings\%USER%\ApplicationData\Microsoft\Proof\eventtriggers.exe

\Documents and Settings\%USER%\ApplicationData\Microsoft\Office\cliconfg.exe

The malware makes the following significant API calls:

- LoadLibrary

- GetProcAddress

- Virtualalloc

The malware executable checks to see if it is running in a VM environment and also ensures that the host on which it is installed is connected to the Internet (failing which it will not run).

The malware also exhibits persistence by creating the following autorun entry in the registry:

HKEY_USERS\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run dfrgntfs.exe Unicode C:\Documents and Settings\user\Application Data\Sun\Java\Deployment\SystemCache\6.0\9\typeperf.exe* success or wait 1 B8EF5F RegSetValueExA

HKEY_USERS\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings\Zones\3 2500 dword 3 success or wait 1 DAEF5F RegSetValueExA

HKEY_USERS\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings DisableCachingOfSSLPages dword 1 success or wait 1 DAEF5F RegSetValueExA

HKEY_USERS\Software\Microsoft\Internet Explorer\Main NoProtectedModeBanner dword 1 success or wait 1 DAEF5F RegSetValueExA

The malware then augments system processes to hinder its removal, once again for persistence:

328 C:\WINDOWS\system32\wscntfy.exe B30000 344064 D4 1E 5E EA 74 1E 9F 25 F9 CC 18 A3 28 FD 93 C3 1E 78 1D 8C AC 81 22 5F D3 DF AB 7E 34 3E 49 B5 D4 7A 45 F5 5D 15 72 6E 0F 93 F6 4C 2F E6 6D 31 16 6C E1 DD BB 23 F7 71 6D 06 A7 40 D7 A7 EB FE 12 70 30 28 92 BD 7F 1D 41 BE 44 5F 38 97 F5 27 E9 14 29 96 D1 28 05 C5 E5 D4 C8 72 94 D8 6A 11 EF 63 1D B4 89 A5 B8 FE 23 F2 1E C0 71 0E 18 7D 5B 74 B7 20 A1 5A 5F CE 27 FC 53 7E E7 D7 55 72 31 BA 28 54 33 25 22 88 A2 15 45 59 CE A5 CF 64 23 A7 AB E3 A4 4C C4 08 79 FC 5C BE 9C D1 FE 87 58 22 A4 B5 7D 64 29 E4 30 EC 87 D3 5D 1F F5 2B 4F A9 56 42 B9 6C B2 77 BD 90 C5 42 39 03 9E FD 93 E1 91 42 AF F8 1B 69 FD 2A 5E 5B 02 0A B4 6D FE FE 73 0C AE 6C AD D6 36 C3 6D EA 48 B5 85 58 E3 94 81 07 09 18 66 9F 63 79 8F C4 3D B1 CB D3 72 6C 45 4B 9B A3 3C 44 0B 61 57 98 7D 98 83 success or wait 1 DA8FB2 WriteProcessMemory

1612 164 7C8106E9 DC5A7B C:\WINDOWS\explorer.exe success or wait 1 CC004D CreateThread

Scope of the threat and impact

Further evidence of this being Caphaw exists in the banking information that it is listening for once it is injected into key Windows Processes. Amongst all samples analyzed, we found the following 24 major banks' sites were actively being monitored by the infection primarily to seek out the victim's online banking credentials. This is based on data pulled from an added thread to explorer.exe process.

- Bank of Scotland

- Barclays Bank

- First Direct

- Santander Direkt Bank AG

- First Citizens Bank

- Bank of America

- Bank of the West

- Sovereign Bank

- Co-operative Bank

- Capital One Financial Corporation

- Chase Manhattan Corporation

- Citi Private Bank

- Comerica Bank

- E*Trade Financial

- Harris Bank

- Intesa Sanpaolo

- Regions Bank

- SunTrust

- Bank of Ireland Group Treasury

- U.S. Bancorp

- Banco Mercantil, S.A.

- Varazdinska Banka

- Wintrust Financial Corporation

- Wells Fargo Bank

|

| Strings found in explorer thread added by Capchaw |

ThreatLabZ continues to monitor the Internet for this threat and it's propagation. The lab is also engaged currently in dissecting this threat further in order to obtain more information about its attack methodology, scope and impact.

Written by Sachin Deodhar & Chris Mannon (ThreatLabZ)