Introduction

Zscaler ThreatLabZ closely monitors exploit kit activity and we have seen some interesting trends in RIG Exploit Kit behavior recently, including a significant spike in cases observed in the wild. We specifically saw large upticks in the closing weeks of January.

|

| Fig 1 - RIG Blocks over 2 Months |

While trying to replicate some of the cases in our testing VMs, we found an infected site suddenly began serving Nuclear EK, and we noticed it doing so via a Keitaro Traffic Distribution System campaign. We have been monitoring these actors since, and in this blog we will briefly describe the activity seen among these campaigns of Keitaro, RIG, and Nuclear.

Keitaro TDS

Traffic Distribution Systems are software and service packages that do pretty much what the name says: their primary function is to intelligently route web traffic that arrives at the TDS operator controlled server. This is not to say they don't have any other functionality, major TDS packages like Keitaro actually provide a great deal of flexibility and control, and malware and exploit kit operators take significant advantage of these features.

In an industry that generally prefers to keep operational and functional details under wraps, Keitaro is an interesting beast that doesn't shy away from the public eye. Keitaro not only has a readily accessible public website with what appears to be a reasonable cost and easy purchase process, there is also a full online help section and an online demo!

|

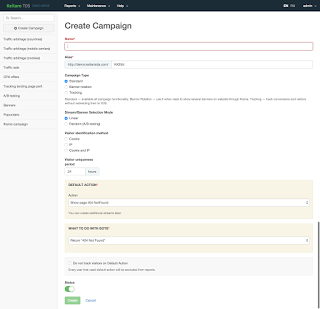

| Fig. 2 - Keitaro TDS Dashboard |

Overview

Keitaro has many features and options, and we don't want to recreate the online help files, so we will only cover some of the basics with few other interesting highlights. This TDS operates on highly-customizable campaigns which come in three flavors: standard redirects, banner serving, and simple impression tracking. These campaigns can have multiple "streams" chosen by linear or randomized selection, and can identify users by IP and/or cookie and enforce unique hits on them across variable timeframes.

|

| Fig 3 - Keitaro TDS Campaign Creation |

Besides identifying users by IP and cookies, Keitaro can make decisions based upon a wide variety of features including:

- browser version

- geographic location

- OS/platform

- Mobile carrier

While we can't say which specific rules have been set up by the operators of this instance of Keitaro, we have seen some behaviors mentioned above (especially blocks on repeat attempts from the same source IPs) in addition to the gate serving both RIG and Nuclear at different times.

Observations

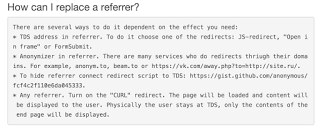

So far, we have described a system that seems perfectly above-board, however Keitaro has some features that appear to be designed specifically for bad-actors such as EK operators. One major feature recently highlighted by Kafeine is the addition of AV checks. This feature allows the TDS operator to make sure none of the payloads being served are detected by AV vendors. Conveniently, they integrate with services that don't share samples with the AV industry. Additionally, there is a section in the help files that specifically details how to break referer chains. This is a feature that directly impacts the ability of researchers to trace activity chains and connect exploit kit instances back to the originating site.

|

| Fig 4 - Keitaro TDS Help Information |

While Keitaro appears to be very powerful and highly polished product, we spotted some interesting misconfiguration side effects from this campaign. Early on in our monitoring, the TDS would attempt to direct repeat visitors to "www.yahoo.com" using a 302 redirection. It turned out that, lacking the scheme portion of the URL, the redirect ended up sending users to the login page of the Keitaro admin panel. This is illustrated in the screenshot below, where an infected page has two injections for the Keitaro gate. The first injection yields a RIG cycle and the second improperly attempts to redirect to Yahoo.

|

| Fig 5 - Keitaro TDS Redirecting to Admin Panel |

Another misconfiguration case we saw may have been an issue more related to the EK infrastructure than on the TDS itself, but one visit to an infected site yielded a redirect to an invalid RIG URL: hxxp://out%2520of%2520datedate/?apitoken=l3SKfPrFJx_ESYjCJunFSrdObkXRFh-BxoubkOM

Despite the occasional misconfigurations seen in this Keitaro instance, it has proven to be a significant source of traffic for both RIG and Nuclear.

|

| Fig 6 - Keitaro Traffic over 30 days |

RIG

The RIG Exploit Kit has been very active in recent weeks, and we have identified multiple campaigns with some varying tactics. We've seen a few cases of malvertising and multiple styles of gates including the occasionally misconfigured Keitaro already discussed..

Gates

In recent behavior, we have seen two primary types of gates being used besides Keitaro. The first was the common gate that has been seen in RIG campaigns for some time. The second was a series of gates that followed a pattern of using the same second level domain across four top level domains, rotating the second level names roughly every 24 hours.

Common RIG Gate

We don't have a clever name for this gate, but it's a familiar pattern, with a number of features at malware-traffic-analysis.net. It uses a host naming scheme similar to the infrastructure that actually delivers RIG landing pages and payloads: a two letter third level domain on top of what appear to be domain-shadowed accounts at Godaddy. The URL path in each case is a randomized .php filename with no parameters.

Quad Power Gate

Due to their use of the same second-level name across four TLD's, we are calling this the Quad Power Gate. This gate utilizes the TLDs .win, .top, .party, and .bid. Though the operators of this gate cycled the hostnames frequently, the path used for the gate's URLs has only changed twice. The first hits seen on the Zscaler network were to domain.tld/persil.php, but we later saw domain.tld/deliner.php. Beginning on the 23rd of February, we the gate began using the filenames "magnum.php" and "puerto.php".

|

| Fig 7 - Quad Power Gate Repeatedly Serving RIG |

While a casual glance at the content returned by the gate might lead one to believe it's simply serving a jQuery script, the truth is that a RIG iframe is actually hidden between large blocks of Javascript. This gate also turns out to be a repeat offender, not only because we found its presence in a number of infected sites, but the gate has a tendency to repeatedly refresh itself, generating one RIG impression after the other. Although we could not confirm any specific instances, we believe this gate to have been used in malvertising attacks as well.

Landing Pages

RIG landing pages, much like the URL pattern used, has not changed too much. The landing page basically consists of one large blob, with multiple script objects, and several layers of encoding and obfuscation.

|

| Fig 8 - Exceprt from RIG Landing Page |

Payloads

Execution is achieved on victim machines via two primary paths: first the usual IE/VBScript God Mode exploit (CVE-2014-6332), and second a large and highly obfuscated Flash payload. Despite the complexity of the protections employed, they are not using the Diffie Hellman-based protection for triggers and shellcode stages. The Flash payload appears to focus on CVE-2015-5122

As for malware, we have recently seen Tofsee being delivered by RIG.

|

| Fig 9 - Strings Decoded from Binary Data in RIG Payload |

Nuclear

Like RIG, the Nuclear Exploit Kit is a prolific threat to web surfers. However, it maintains its position in the EK hierarchy, being more sophisticated than RIG yet not quite as cutting-edge as Angler. As an illustration of this point, we have not yet seen Nuclear adopt the latest Silverlight exploit that Angler recently debuted.

|

| Fig 10 - Nuclear Blocks over 2 Months |

Gates

Besides the Keitaro gates, we have seen one prolific gate pattern over all else. The operators of this campaign seem to use infected sites which then redirect to the Nuclear landing page. We have seen some very interesting cases of this gate, including one site apparently owned by a bicycle shop in the UK. In this instance, the gate injection was served via the shop's Ebay page, in requests for embedded images.

|

| Fig 11 - Nuclear Gate Inject in Image from Ebay Listing |

Landing Pages

Nuclear's landing page continues to utilize data stored in various HTML elements, which is then parsed by scripts to identify browser and plugin features and determine the execution flow.

|

| Fig 12 - Nuclear Landing Page Excerpt |

Payloads

Nuclear continues the trend of delivering single file Flash payloads, with multiple secondary payloads: one each for Flash versions <18.0.0.203, <19.0.0.207, and higher. We saw an interesting change between the method used to transition to the secondary payloads.

The initial first-stage SWF used a complicated execution flow with the three payloads being constructed across multiple functions. In each case, two separate arrays of bytes are combined before a version-specific XOR key is used for the "final" payload. We use quotes around "final" because Nuclear continues to utilize a Diffie Hellman protocol to protect the actual exploit trigger and shellcode stage.

|

| Fig 13 - Nuclear Stage 1 Payload Obfuscation |

The latter first-stage Flash payload dispensed with all of the complicated reconstruction, and simply uses base64-encoded strings to encode the second-stage SWFs. The second-stage payloads, however, were almost identical to those found in the previous iteration as shown below.

|

| Fig 14 - Nuclear Stage 2 Payload Comparison |

The second stage exploits appeared to be CVE-2015-5122 for Flash <18.0.0.203, CVE-2015-7645 for <19.0.0.207, and the "default" case of CVE-2015-8651 for anything newer. Besides the Flash exploits, we also saw CVE-2013-2551 for direct exploitation of IE.

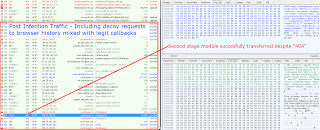

Following succesful exploitation, we have seen Dofoil being installed. The screenshot below shows its signature pattern of decoy GET and POST requests to URLs in the browser history with a few actual callbacks mixed in. The command & control server even uses 404 error codes to attempt to mask the nature of the callback activity.

|

| Fig 15 - Nuclear Cycle Including Dofoil Callback and Decoy Traffic |

Conclusion

Though Nuclear and RIG both generate a good deal of impressions via other routes, the Keitaro gate has been a significant source of traffic on its own. It's clear that the flexibility in Keitaro's configuration options make it a powerful partner for the criminal operators of these and other exploit kits. As always, Zscaler ThreatLabZ will continue to monitor Nuclear, RIG, and Keitaro for further developments.