Ever use Google Drive? Of course you have—you and approximately 1 billion other people. And it is estimated that those 1 billion users have loaded more than 2 trillion files on Google Drive. So, it’s a pretty big deal when a cyberattack uses Google Drive to deliver its payload. That’s exactly what was happening with a downloader being tracked by the Zscaler ThreatLabZ team.

As you may know, downloaders are often considered the first stage of infection. They usually contain obfuscated codes to download the actual payload. Sometimes they also have some anti-debugging and evasion techniques to safeguard the actual payload from being detected by anti-malware programs. Downloaders often provide attackers with the ability to gain an initial foothold in the system.

The Zscaler ThreatLabZ team was tracking a highly obfuscated downloader known as Win32.Downloader.EdLoader (the name was given by a Zscaler ThreatLabZ researcher) that has employed some anti-analysis techniques to make analysis more difficult and has been actively spreading during the past few months via a different mechanism. The interesting part of this downloader is that it is leveraging Google Drive to download the final payload.

In this blog, we’ll share our analysis of a campaign using a vulnerability exploit in the initial phase and its use of Google Drive to download a different password stealer in the later phase.

Figure 1: Samples observed in the Zscaler cloud.

The spreading mechanism

This downloader basically comes into the system via spamming campaigns.

During the past few months, we’ve seen multiple spam campaigns featuring various email templates having language specific to the country being targeted.

Figure 2: Geographical regions hit by the infection.

Let’s take a look at how the mechanisms that help the infection spread.

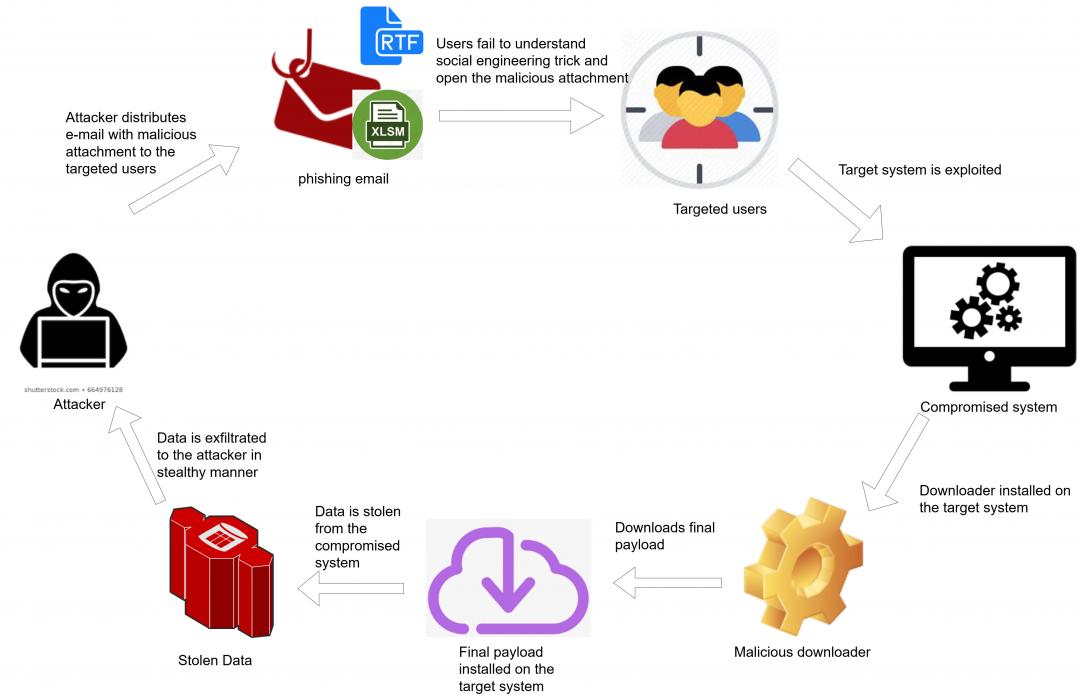

Figure 3: The workflow of the infection chain.

The user receives an email from the attacker, which contains the malicious attachment in either RTF or XLSM format.

Figure 4: The email template a user receives.

This malicious attachment of the RTF document contains Excel sheets that leverage the CVE-2017-8570 vulnerability exploit to download the initial payload into the victim’s machine.

Figure 5: The RTF document with the embedded object.

The CVE-2017-8570 vulnerability exploit makes use of a composite moniker in the RTF document to execute a scriptlet of an XML file wrapping the VBScript. In this case, the RTF document has two ObjData files, one of which has an SCT file encoded. This SCT file is then dropped into the %TEMP% folder and executed by a second ObjData file embedded in the RTF document.

Figure 6: The SCT file with an XML scriptlet wrapping the VBScript.

The SCT file contains a hardcoded URL encrypted with a Base64, downloads the initial payload via a PowerShell command and saves it into the %APPDATA% folder, then executes it.

Figure 7: PowerShell command from the SCT file.

A few of the malicious attachments are XLSM files having obfuscated malicious macros with the function Sub Auto_Open(). When a victim opens the Excel file, a macro code will be automatically executed. Here also, similar to SCT files, a hardcoded URL is being used to download the initial payload and is executed via a PowerShell command.

Figure 8: The XLSM file with the malicious macro code.

The initial payload is the newly crafted downloader, which uses the shellcode to download the final payload. The final payload is encrypted with a custom algorithm that is decrypted and executed by the shellcode present in the initial downloader.

Downloader analysis

We have successfully tracked down the request and discovered more information about how this downloader works.

It first injects itself into one of the following system processes—RegAsm.exe, MSBuild.exe and RegSvcs.exe—or self-injects using the process hollowing technique.

Anti-analysis—This downloader uses different anti-analysis techniques:

- It enumerates all top-level windows on the screen using the EnumWindows API to identify sandbox/emulators. If the count of windows is less than 12, it terminates itself.

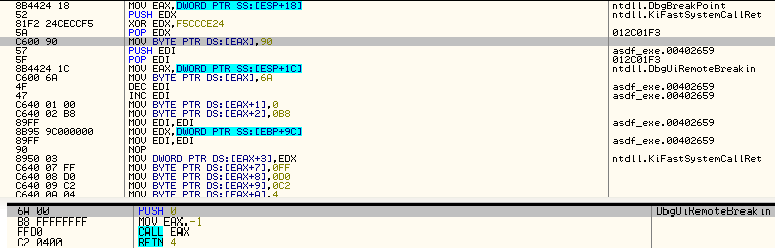

- It patches the DbgBreakPoint and DbgUiRemoteBreakin Windows APIs as an anti-debugging measure.

Figure 9: The patched DbgUIRemoteBreakin API.

- It tries to detach from the attached debugger using the NtSetInformationThread Windows API and an undocumented thread information class - ThreadHideFromDebugger (0x11).

Figure 10: The NtSetInformationThread API.

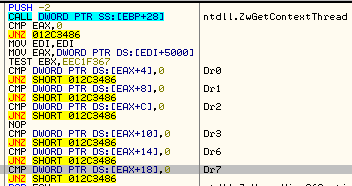

- It checks for debug registers.

Figure 11: The debug registers.

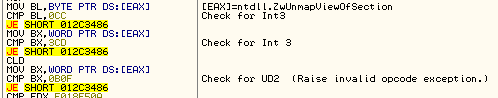

- Before making a call to some Windows APIs, it also checks for a breakpoint instruction in the API code.

Figure 12: Checking for a breakpoint instruction.

Payload download and installation

It downloads an encrypted payload. During our analysis, we found different variants that download the payload from Google Drive as well.

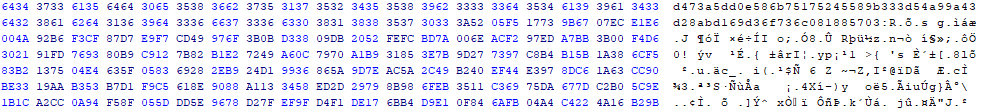

Figure 13: A snapshot of the encrypted payload.

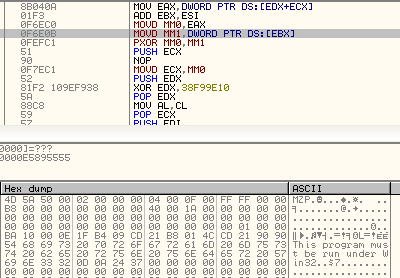

It uses a simple XOR encryption, and the decryption key is hardcoded. We found different variants using different XOR keys.

Figure 14: The XOR decryption.

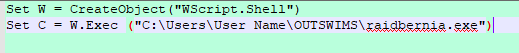

The decrypted payload is mapped and executed in the sample process. Depending on the configuration in the shellcode, the downloader copies itself to the %USERPROFILE% directory. That is where it dropped the two files—self copy and VBScript files—that execute it.

Figure 15: The VBScript code.

Persistence

It creates a run registry key, which points to the VBScript files:

HKEY_USERS\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnce

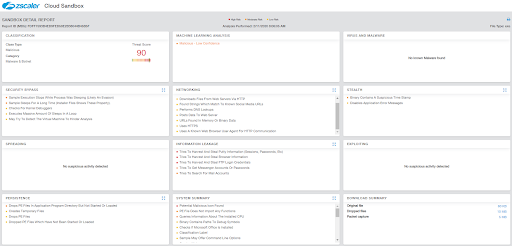

Figure 16: Zscaler Cloud Sandbox detected the downloader.

Conclusion

Malicious downloaders have been using advance techniques over the years, but the end goal remains the same - getting malware onto a user’s system. And using a popular user tool, such as Google Drive, to download a malicious payload can infect a large number of machines. The Zscaler ThreatLabZ team continuously monitors and blocks malicious downloaders and other types of advance malware to ensure the protection of our customers.

IOCs

|

EDLoader Hash |

Downloaded Malware |

|

e78f619305b9884de720bd3b980bede6 |

Win32.Backdoor.NetwiredRC |

|

a1ac955ae6af1910309233788356726d |

Win32.Backdoor.AgentTesla |

|

5ab142bbb2fc9c033b57e7cdda9f6a78 |

Win32.Backdoor.RemcosRAT |

|

dadfb5780b0492f765d0900d76daf494 |

Win32.Backdoor.Predatorlogger |

|

b7f69192280bbc13e44069c11f260c41 |

Win32.Backdoor.Nanocore |

|

6ea19c5e7a0808ac26581ca386044fad |

Win32.PWS.Vidar |

|

fdff7593b4ed9fed58e2b38044b45b5f |

Win32.PWS.Azorult |

|

759d976d6094acd420a16574475d3cc1 |

Win32.PWS.Avemaria |

|

c4714065dfa9a6f48e28fcc3a41bf3ce |

Win32.PWS.Kpot |

|

c004fbe61ff4d8013b63cf3548364ecb |

Win32.PWS.Avecaesar |

|

72218b21016889d1082b49fd21b0cda7 |

Win32.PWS.Raccoon |

|

edd4b40d55884ad6d8ffa11d5e13a5e7 |

Win32.PWS.Lokibot |