Summary

ThreatLabz has discovered a new strain of a large-scale phishing campaign, which uses adversary-in-the-middle (AiTM) techniques along with several evasion tactics. Similar AiTM phishing techniques were used in another phishing campaign described by Microsoft recently here.

In June 2022, researchers at ThreatLabz observed an increase in the use of advanced phishing kits in a large-scale campaign. Through intelligence gathered from the Zscaler cloud, we discovered several newly registered domains that are used in an active credential-stealing phishing campaign.

This campaign stands out from other commonly seen phishing attacks in several ways. It uses an adversary-in-the-middle (AiTM) attack technique capable of bypassing multi-factor authentication. There are multiple evasion techniques used in various stages of the attack designed to bypass conventional email security and network security solutions.

The campaign is specifically designed to reach end users in enterprises that use Microsoft's email services. Business email compromise (BEC) continues to be an ever-present threat to organizations and this campaign further highlights the need to protect against such attacks.

In this blog, we describe details of the tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) involved in the campaign.

Since the campaign is active at the time of blog publication, the list of indicators of compromise (IOCs) included at the end of the blog should not be considered an exhaustive list.

Key points

- Corporate users of Microsoft's email services are the main targets of this large-scale phishing campaign.

- All these phishing attacks begin with an email sent to the victim with a malicious link.

- The campaign is active at the time of blog publication and new phishing domains are registered almost every day by the threat actor.

- In some cases, the business emails of executives were compromised using this phishing attack and later used to send further phishing emails as part of the same campaign.

- Some of the key industry verticals such as FinTech, Lending, Insurance, Energy and Manufacturing in geographical regions such as the US, UK, New Zealand and Australia are targeted.

- A custom proxy-based phishing kit capable of bypassing multi-factor authentication (MFA) is used in these attacks.

- Various cloaking and browser fingerprinting techniques are leveraged by the threat actor to bypass automated URL analysis systems.

- Numerous URL redirection methods are used to evade corporate email URL analysis solutions.

- Legitimate online code editing services such as CodeSandbox and Glitch are abused to increase the shelf life of the campaign.

Phishing campaign overview

Beginning in June 2022, ThreatLabz observed a sharp increase in advanced phishing attacks targeting specific industries and geographies.

We identified several newly registered domains set up by the threat actor to target Microsoft mail services' users.

Based on our cloud data telemetry, the majority of the targeted organizations were in the FinTech, Lending, Finance, Insurance, Accounting, Energy and Federal Credit Union industries. This is not an exhaustive list of industry verticals targeted.

A majority of the targeted organizations were located in the United States, United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia.

After analyzing the large volume of domains used in this campaign, we identified some interesting domain name patterns which we highlight below.

Domains spoofing Federal Credit Unions

Some of the attacker-registered domains were typosquatted versions of legit Federal Credit Unions in the US.

|

Attacker-registered domain name |

Legit Federal Credit Union domain name |

|

crossvalleyfcv[.]org |

crossvalleyfcu[.]org |

|

triboro-fcv[.]org |

triboro-fcu[.]org |

|

cityfederalcv[.]com |

cityfederalcu[.]com |

|

portconnfcuu[.]com |

portconnfcu[.]com |

|

oufcv[.]com |

oufcu[.]com |

Note: Per our analysis of the original emails using the Federal Credit Union theme, we observed an interesting pattern. These emails originated from the email addresses of the chief executives of the respective Federal Credit Union organizations. This indicates that the threat actor might have compromised the corporate emails of chief executives of these organizations using this phishing attack and later used these compromised business emails to send further phishing emails as part of the same campaign.

Domains spoofing password reset theme

Some of the domain names used keywords related to "password reset" and "password expiry" reminders. This might indicate that the theme of the corresponding phishing emails was also related to password reset reminders.

expiryrequest-mailaccess[.]com

expirationrequest-passwordreminder[.]com

emailaccess-passwordnotice[.]com

emailaccess-expirynotification[.]com

It is important to note that there are several other domains involved in this active campaign, some of them are completely randomized while others do not conform to any specific pattern.

Distribution mechanism

We have limited visibility into the emails used to distribute the phishing URLs. In some cases, the malicious links were sent directly in the email body; in other cases, the link was present inside the HTML file attached to the email.

Figure 1 below shows an email which contained an HTML attachment with the malicious phishing URL embedded inside it.

Figure 1: phishing email sent to the user with HTML attachment

Figure 2 below shows the contents of the HTML attachment. It uses window.location.replace() to redirect the user to the phishing page when the HTML page is opened with the browser.

Figure 2: HTML attachment used to redirect the user to the phishing page

Figure 3 below shows an example of a phishing email in which the attacker sent the malicious link directly in the email body.

Figure 3: Malicious link present in the email body

We observed the use of a variety of URL redirection methods in a large number of cases. Instead of sending the actual phishing URL in the email, the attacker would send links that used a variety of redirection methods to load the final phishing page URL. We describe the details of some of these methods in the following section.

Abuse of legitimate web resources for redirections

Phishing sites were seen being delivered, redirected into, and hosted using numerous methods.

A common method of hosting redirection code is making use of web code editing/hosting services: the attacker is able to use those sites, meant for legitimate use by web developers, to rapidly create new code pages, paste into them a redirect code with the latest phishing site’s URL, and proceed to mail the link to the hosted redirect code to victims en masse.

These services provide flexibility to the attackers, since the contents of the redirect codes can be changed at any time. It has been observed that in the midst of a campaign, attackers will modify the code of a redirect page and update a phishing site’s URL that has been flagged as malicious, to a fresh undetected URL.

The most commonly abused service for this purpose is CodeSandbox.

Figure 4 below shows the most common redirect code hosted on CodeSandbox, utilized by the phishing site.

Figure 4: redirect code snippet on an attacker-controlled CodeSandbox instance

Figure 5 below shows an example of redirect code hosted on a similarly abused service - Glitch.

Figure 5: redirect code hosted on an attacker-controlled Glitch instance.

Many dozens, if not hundreds, of different CodeSandbox code pages were observed hosting different redirect codes to the phishing sites.

Many of those pages were authored by a network of registered CodeSandbox users, letting us see the names of the Google accounts used for their registration.

While most Google accounts we could find are anonymous throwaway accounts that are a dead end to attribution efforts, an internet search of a few account names tie some of the authors to older, more primitive phishing campaigns, and also show a history of engaging in cryptocurrency investment/recovery scams.

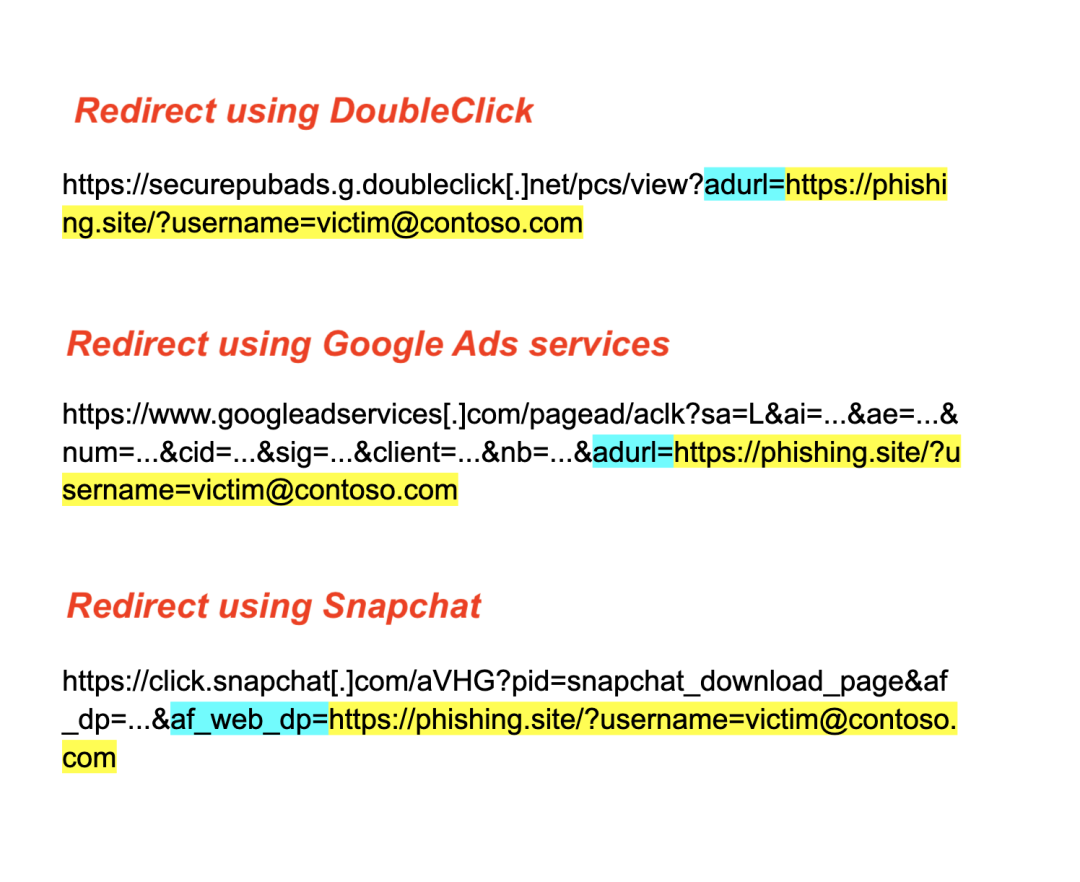

Another method observed for URL redirection is the abuse of Open Redirect pages hosted by Google Ads and Snapchat. Figure 6 shows more details.

Figure 6: different methods of URL redirection abusing Open Redirect pages

Browsing to these links will immediately redirect the client to the URL specified in the GET parameter highlighted in blue colour.

This method gives the attackers the benefit of being able to send emails with links pointing to these legitimate sites as the entry point, with the actual phishing sites’ addresses only appearing somewhere in the GET parameters, raising the likelihood of evading scanning of malicious URLs performed by email clients.

Fingerprinting-based evasion

This campaign utilizes a client fingerprinting process on all phishing sites that we will cover in this article. This process happens immediately upon the page being visited.

The initial page clients are served consists of JavaScript code, ripped from the FingerprintJS project, whose purpose is to collect information from the client’s browser in order to help the site determine if the person behind the browser is in fact not an unsuspecting victim, but an unwelcome probing analyst or an automated bot.

The script gathers identifying information such as the client’s operating system, screen dimensions, and timezone, and communicates its findings back to the site by WebSocket traffic. The complete list of information gathered from the client's machine is mentioned in the Appendix at the end of the blog.

Figure 7: Client fingerprint data sent to the server over websocket

With this information received, the site arrives at a verdict whether it should continue reeling in the client, or should it get rid of it by redirecting to the Google homepage.

How exactly the site decides this is unknown since the logic is present on the server side, but it has been observed that browsers running in virtual machines are detected by examining the name of the client’s graphics driver, as exposed by the WebGL API.

By default, VirtualBox and VMware make themselves known this way, and require some masking effort in order to pass this check, for example making use of browser setting `webgl.override-unmasked-renderer` on Firefox.

In case the site does not find a reason to suspect the client, it will serve it an authentication cookie that the client-side code will proceed to save before reloading the same page, this time receiving the main phishing page by the site.

Figure 8: Upon successful fingerprint process, site returns authentication cookie __3vjQ.

Proxy-based AiTM phishing attack overview

Traditional credential phishing sites collect the user's credentials and never complete the authentication process with the actual mail provider's server. If the user has multi-factor authentication (MFA) enabled, then it prevents the attacker from logging into the account with only the stolen credentials.

In order to bypass multi-factor authentication, attackers can use Adversary-in-the-middle (AiTM) phishing attacks. All the attacks which we describe in this article used the AiTM phishing attack method.

AiTM phishing attacks complete the authentication process with the actual mail provider's server (in this case - Microsoft), unlike traditional credential phishing kits. They achieve this by acting as a MiTM proxy and relaying all the communication back-and-forth between the client (victim) and the server (mail provider).

There are three main open-source AiTM phishing kits available which are widely known in the community.

- Evilginx2

- Muraena

- Modlishka

Based on our research, we believe that the threat actor in this case used a custom phishing kit. In the following section, we highlight some of the unique attributes we identified in the client-server communication which differs from the common off-the-shelf AiTM phishing kits.

We will not cover the technical details of how the AiTM phishing kits work in general since they are widely documented in the public domain such as here.

Unique attributes of the phishing kit

All advanced AiTM kits have in common that they operate as a proxy between the victim and the target site (Microsoft servers in our case).

The kits intercept the HTML content received from the Microsoft servers, and before relaying it back to the victim, the content is manipulated by the kit in various ways as needed, to make sure the phishing process works.

We observed several ways in which the phishing kit’s operation is distinguishable from the three open-source kits:

HTML parsing

It’s apparent that the phishing kit’s backend is making use of an HTML parser library, such as Beautiful Soup.

We can deduce this by comparing the messy, unindented HTML code arriving from Microsoft:

And the same HTML code as relayed by the phishing kit, tidied up and properly indented:

It is likely that the phishing kit feeds the HTML it reads from the Microsoft server into an HTML parser, which creates a programmatic representation of the entire HTML tree. This allows a programmer to conveniently manipulate the different elements by interacting with the objects that represent them.

Once the manipulation is done, the library produces an HTML output of the tree with all changes applied. This often results in a tidy output, as we see above.

The three open-source kits don’t make use of HTML parsers, instead operating on the received HTML data just by using basic string operations.

Domain translation

One of the things the kits need to take care of is replacing all the links to the Microsoft domains with equivalent links to the phishing domain, so that the victim remains communicating with the phishing site throughout the phishing session.

For example, Figure 9 below shows a side-by-side comparison of an HTML snippet. On the left is the original code as served by Microsoft, and on the right is the same code after it has undergone translation, on its way to be relayed to the victim.

Figure 9: HTML snippets before and after translation

The original subdomain (green), the original domain name (blue, minus the TLD), and a unique generated ID (pink) are joined together with dashes and become a subdomain under the phishing site’s domain (orange).

This translation pattern, namely the 8 hexadecimal digits ID added to links, appears unique to this phishing kit, and is not used by the three open-source kits.

However, there’s a case where this translation is not taking place.

The Office 365 login page, as part of a feature called “Azure Active Directory Seamless Single Sign-On”, communicates with Microsoft server `autologon.microsoftazuread-sso.com` in order to load company-specific scripts to offer this feature to the authenticating client.

The references to this server can be seen in this snippet of JavaScript, taken from the main Office 365 login page:

For one reason or another, the phishing kit does not perform translation on the links to `autologon.microsoftazuread-sso.com` shown above, and they make their way to the victims intact.

This results in the victim’s browser performing HTTP requests like the following, while loading the login page:

Effectively “leaking” the phishing site’s address as the referring site inside a request to the Microsoft server.

This opens up the possibility of detecting the kit in the act, if a victim’s HTTP traffic is monitored by network security solutions capable of deep packet inspection.

Post-compromise activity

To investigate the post-compromise activity, we set up an Azure AD instance in our lab with a dummy account and a domain controlled by us. We visited one of the live phishing URLs, supplied dummy account credentials, and completed the multi-factor authentication process.

In one case, we observed that the attacker logged into our account, 8 minutes after we sent our credentials to the attacker's server. It is important to note that the attacker logged into the account from another IP address (different from the phishing domain's IP address). Based on the delay of 8 minutes in post-compromise activity, we suspect that the threat actor is manually logging into the account.

Figure 10 below shows audit / sign-in logs from our lab's Azure AD highlighting the post-compromise activity.

Figure 10: Azure AD sign-in logs highlighting post-compromise activity

At the time of our investigation, we did not see any specific post-compromise activity performed by the threat actor besides merely logging into the account, reading emails and checking the user's profile information.

Zscaler’s detection status

Zscaler’s multilayered cloud security platform detects indicators at various levels, as seen here:

Conclusion

Business email compromise (BEC) continues to be one of the top threats which organizations need to protect against. As described in this blog, the threat actors are constantly updating their tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) to bypass various security measures.

Even though security features such as multi-factor authentication (MFA) add an extra layer of security, they should not be considered as a silver bullet to protect against phishing attacks. With the use of advanced phishing kits (AiTM) and clever evasion techniques, threat actors can bypass both traditional as well as advanced security solutions.

As an extra precaution, users should not open attachments or click on links in emails sent from untrusted or unknown sources. As a best practice, in general, users should verify the URL in the address bar of the browser before entering any credentials.

The Zscaler ThreatLabz team will continue to monitor this active campaign, as well as others, to help keep our customers safe.

Indicators of compromise

# Since the campaign is active at time of the publication and this threat actor is relentless in creating new domains almost every day, the IOCs below should not be considered as an exhaustive list.

The complete list of IOCs can be found at our GitHub repository here: https://github.com/threatlabz/iocs/blob/main/aitm_phishing/microsoft_iocs.txt

Appendix

Client fingerprint collected

{u'data': {u'appCodeName': <string>,

u'appName': <string>,

u'audioCodecs': {u'aac': <string>,

u'm4a': <string>,

u'mp3': <string>,

u'ogg': <string>,

u'wav': <string>},

u'automation': [<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>,

<boolean>],

u'battery': <boolean>,

u'cookieEnabled': <boolean>,

u'debugTool': <boolean>,

u'devtools': <boolean>,

u'document': {u'characterSet': <string>,

u'charset': <string>,

u'compatMode': <string>,

u'contentType': <string>,

u'designMode': <string>,

u'hidden': <boolean>,

u'inputEncoding': <string>,

u'isConnected': <boolean>,

u'readyState': <string>,

u'referrer': <string>,

u'title': <string>,

u'visibilityState': <string>},

u'etsl': <integer>,

u'hardwareConcurrency': <integer>,

u'hasChrome': <boolean>,

u'javaEnabled': <boolean>,

u'language': <string>,

u'languages': [<string>, <string>],

u'mediaSession': <boolean>,

u'mimeTypes': [<string>, <string>],

u'multimediaDevices': {u'micros': <integer>,

u'speakers': <integer>,

u'webcams': <integer>},

u'permissions': {u'accelerometer': <string>,

u'ambient-light-sensor': <string>,

u'ambient_light_sensor': <string>,

u'background-fetch': <string>,

u'background-sync': <string>,

u'background_fetch': <string>,

u'background_sync': <string>,

u'bluetooth': <string>,

u'camera': <string>,

u'clipboard-write': <string>,

u'clipboard_write': <string>,

u'device-info': <string>,

u'device_info': <string>,

u'display-capture': <string>,

u'display_capture': <string>,

u'geolocation': <string>,

u'gyroscope': <string>,

u'magnetometer': <string>,

u'microphone': <string>,

u'midi': <string>,

u'nfc': <string>,

u'notifications': <string>,

u'persistent-storage': <string>,

u'persistent_storage': <string>,

u'push': <string>,

u'speaker-selection': <string>,

u'speaker_selection': <string>},

u'platform': <string>,

u'plugins': [<string>,

<string>,

<string>,

<string>,

<string>],

u'referrer': <string>,

u'screen': {u'cHeight': <integer>,

u'cWidth': <integer>,

u'orientation': <string>,

u'sAvailHeight': <integer>,

u'sAvailWidth': <integer>,

u'sColorDepth': <integer>,

u'sHeight': <integer>,

u'sPixelDepth': <integer>,

u'sWidth': <integer>,

u'wDevicePixelRatio': <integer>,

u'wInnerHeight': <integer>,

u'wInnerWidth': <integer>,

u'wOuterHeight': <integer>,

u'wOuterWidth': <integer>,

u'wPageXOffset': <integer>,

u'wPageYOffset': <integer>,

u'wScreenX': <integer>},

u'serviceWorker': <boolean>,

u'timezone': <string>,

u'userAgent': <string>,

u'vendor': <string>,

u'videoCodecs': {u'h264': <string>,

u'ogg': <string>,

u'webm': <string>},

u'visitorId': <string>,

u'webRTC': <boolean>,

u'webXR': <boolean>,

u'webgl': <string>},

u'ftype': <string>}